When it comes to the laws of nature—be it a changing climate, the atmospheric physics of a hurricane, or the chemistry behind toxic chemicals leaching into the soil—socioeconomic factors including race, location, education, economic resources, and health can make communities and entire regions more vulnerable. The U.S. Gulf South is a case in point.

Arcing along the northern edge of the Gulf of Mexico, the states comprising this region have some of the highest health disparities, highest percentages of persons in poverty, and highest densities of Black, African American, Hispanic, and Latino populations in the U.S., according to data available through the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) and U.S. Census figures.

This region also is the nexus for natural disasters including hurricanes, tornadoes, and coastal flooding, based on data from the National Center for Disaster Preparedness (NCDP). In addition, a government study of the location of hazardous waste landfills in eight Southern states conducted in the 1980s found a disproportionate number of these sites located in high-poverty areas that were home to predominately Black communities.

But data, especially NASA's openly-available Earth observation data, are a powerful tool communities can use to bring greater equity and environmental justice to vulnerable regions. Multiple related NASA-funded projects are accomplishing this in the Gulf South.

NASA and Environmental Justice

As noted by the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council, environmental justice (EJ) refers to the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.

Going further, “environmental justice communities” are geographic locations within the U.S. and its territories with high concentrations of persons of color, households with low-income, or community members who are indigenous or members of Tribal nations where residents experience or are at risk of experiencing higher or more adverse human health or environmental impacts.

As part of the commitment by NASA’s Earth Science Division (ESD) to equity and environmental justice, ESD developed an Equity and Environmental Justice (EEJ) strategy. A recent ESD funding opportunity, Research Opportunities in Space and Earth Science (ROSES)-2021, A.49 Earth Science Applications: Equity and Environmental Justice, was designed to advance progress on EEJ domestically through the application of Earth science, geospatial, and socioeconomic information.

One project funded under this solicitation was the Assessment of the Gulf Coast Environmental Justice Landscape for Equity (AGEJL-4-Equity). After completion of the assessment, NASA's Earth Science Data Systems (ESDS) Program in collaboration with the agency's Open Source Science Initiative extended support to enable the project team to foster EEJ community engagement with NASA Earth observation data for residents of this region.

"The new project title, Advancing Gulf Coast Environmental Justice and Leadership and Engagement in Open Science (AGEJLE-OS), is the perfect example of how open science is enabling equity and environmental justice projects to directly empower communities by making data more findable, impactful, and meaningful," says Dr. Yaitza Luna-Cruz, an ESDS program executive.

This view is echoed by NASA Chief Science Data Officer Kevin Murphy. "The open sharing of data, tools, and knowledge, both within the scientific community and with the wider public, is more inclusive and accelerates scientific discovery," he says.

The Project and the Team

Data are a primary challenge to advancing environmental justice, and the first phase of the project investigated Earth science data use and data gaps in the Gulf region. “The environmental justice movement in many ways started in the South with the work of Dr. Beverly Wright, who is a co-leader of this project and the founder and executive director of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice (DSCEJ), and Dr. Robert Bullard,” says Dr. Nathan Morrow, an associate professor in the Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine and another co-leader of the project. “The Gulf Coast is the fastest growing coast. It faces the largest disparities in the country in terms of health and socioeconomics. It’s at the forefront of climate change impacts and new threats.”

Along with Wright and Morrow, the project is also co-led by Dr. David Padgett, associate professor of geography at Tennessee State University. The project team is collaborating with local communities and with four regional EJ networks: the National Black Environmental Justice Network, the Historically Black College and University-Community Based Organization (HBCU-CBO) Gulf Coast Equity Consortium, the DSCEJ Community Advisory Board, and the Environmental Justice Forum.

Communiversity

The project’s foundation is a model called “Communiversity.” Developed by project co-lead Wright, the Communiversity Model integrates community life experiences regarding environmental justice issues with the theoretical knowledge of academicians. The model ensures that community members have an equal voice with researchers in developing, resourcing, and implementing projects.

Project co-lead Padgett notes that the Communiversity Model creates an equal partnership between community members and researchers and includes actual action. “It’s saying, OK, here’s the situation, here’s what your air quality looks like,” he explains. “How can you as the community, perhaps with some support from your federal agency, nonprofit organization, or university, collectively come to a resolution?”

The Communiversity Model also views community members as consultants in a project rather than volunteers, and provides compensation for their time and effort. “The consultants are being paid and the grad students are being paid and undergraduate students are being paid. And then we expect people in these communities to take up their weekends, Saturdays, evenings for a $50.00 Walmart gift card? That just doesn’t fly anymore,” says Padgett. “If you look at Dr. Wright’s budgets, you’ll see that the community-based organizations are well-compensated and very much incentivized to work. Not that they wouldn’t work anyway, but it’s a much fairer playing field and it leads to sustainability.”

The Data

The project team observes that air, land, and water issues are where NASA data can really make a difference. Data from missions like the recently launched Tropospheric Emissions: Monitoring Pollution (TEMPO) and the upcoming Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, ocean Ecosystem (PACE) and Geostationary Littoral Imaging and Monitoring Radiometer (GLIMR) will provide data that will make it easier to assess environmental conditions across the region.

“For these coastal communities at the boundary areas where humans and the environment are interacting, we need that hyperspectral and high spatial resolution data because we’re right there where it’s all coming together,” says Morrow.

Just providing data, though, is not enough. Community members need to trust the data. Padgett notes that this can be a hurdle in some communities that have an ingrained distrust of the government. He points to an example of a community meeting in Atlanta where he had to overcome their misgivings.

“There was a woman who sat right in the front row; clearly, she was the matriarch of the group. And she said, loudly, why are we working with NASA? They have all these satellites; they spy on us and here we are working with them. I could just see this whole thing going left really quickly,” says Padgett.

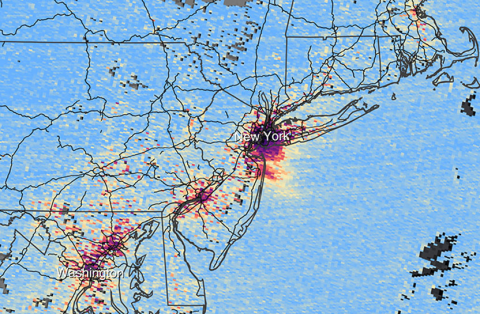

Padgett responded by asking if she had grandchildren. After she said she did, he asked if any of them have asthma. She said yes. Then Padgett pulled up a NASA data layer showing areas with high ozone concentrations and showed that her neighborhood had some of the highest ozone concentrations in the city.

“I pointed out that ozone is much higher where you see these hotspots and that can trigger asthma attacks. And you know that African American children are three times more likely to suffer from asthma. Other children in there are 10 times more likely to die from asthma attacks. At that point she was locked in,” says Padgett. “And this is where we have to understand group dynamics because she was sort of the mother of the community and maybe in other communities. If mother so-and-so says everybody needs to show up at this NASA meeting, trust me, people will show up.”

Padgett points out that one big win for the project is just the exposure of these communities to the benefits of NASA data—making the first step at demystifying these data. In line with the precepts of the Communiversity Model, this communication is both ways, and NASA is listening to the views and needs of the community to ensure that community members will receive and use the data that best meet their needs.

“I think we’re at the precipice of a very interesting time with TEMPO, with the small cubesats and commercial data buys with a high temporal frequency, and hyperspectral imagery like PACE and GLIMR that we’ll be getting the type of data at the type of scales we need to solve human problems,” says Morrow.

Future Work and Next Steps

The nine months spent by the project team assessing environmental justice needs and how NASA data can be integrated into solving these needs have laid a firm foundation for the next phases of the project in which NASA Earth observation data and open science efforts will play important roles. Morrow points to the work of NASA’s Transform to Open Science (TOPS) mission in getting communities to engage in open science and use NASA data assets.

The upcoming TOPS Open Science 101 certification training, a five-module, community-developed open science curriculum designed to introduce open science definitions, tools, and resources, will help the project train 30 to 50 open science certified community-engaged researchers.

“I think that the open science certification will really play into the validation that this science can be the best science in the country,” says Morrow. “It doesn’t necessarily have to come out of an [academic] research institution. It can come out of community organizations that are supported by community-engaged researchers with proper science training and getting community members certified in open science approaches.”

Within NASA, the Applied Remote Sensing Training (ARSET) program is developing training based on the project team’s report, and Morrow observes that the agency is considering many of the eight recommendations in the project’s Executive Summary. The project team also is developing workshops on creating better NASA proposals for supporting EJ initiatives and better proposals in general that rely on NASA Earth observation data.

“Environmental justice is the place where the rubber meets the road on human environmental interactions using NASA data, and I think it just can't be a small investment,” says Morrow. “It needs to be a major investment of thinking through how [data with] new, better temporal scales, better spatial scales, better spectral scales can start to answer these really complicated problems. And now is the time to make the investment.”

NASA's Murphy agrees. "NASA data belong to everyone, and open science enables greater accessibility to these data so communities can use them to make more informed decisions about their environment and their role in it."

NASA Earth Science Data Systems Program EJ Resources

- Environmental Justice Data Catalog

- Environmental Justice at NASA Backgrounder

- Visualization, Exploration, Data, and Analysis (VEDA) Dashboard Environmental Justice Thematic Area

- Understanding Needs to Broaden Outside Use of NASA Data (UNBOUND) for Environmental Justice

- NASA's Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC)