In Indonesia, it is monsoon season. Water parachutes down from tropical clouds to start its journey toward the sea. Rain pours from the sky in slabs of water that slap the sandy ground of the Indonesian Archipelago. Water rolls off the palm fronds and rocks and saturated soil of the islands of Sumatra, Java, and Borneo, flowing into streams and bays and then out into the Java Sea. The fresh water will ultimately mingle into the crowd of salt water, but during the monsoon, enough of it sweetens a plume that spreads out on the Indian Ocean surface. And in turn, rain-freshened waters flow into the straits in Indonesia from the Pacific Ocean to the Indian Ocean.

Rain and fresh water are ingredients in the ocean’s everyday water cycle, but the oceans are a pot that is never completely stirred. Waters are constantly moving and mixing. Like the patterns of pressure and temperature in the atmosphere that create weather conditions, oceans are busy exchanging heat and fresh water to create a water climate. Fresh water floats near the surface, lighter than the cold, salty water that sinks, especially near the North and South Poles, causing both vertical circulation and a conveyor belt-like circulation of salty and cold water around the globe. The ocean trades its heat with the atmosphere too, helping stabilize the climate patterns that shape our world.

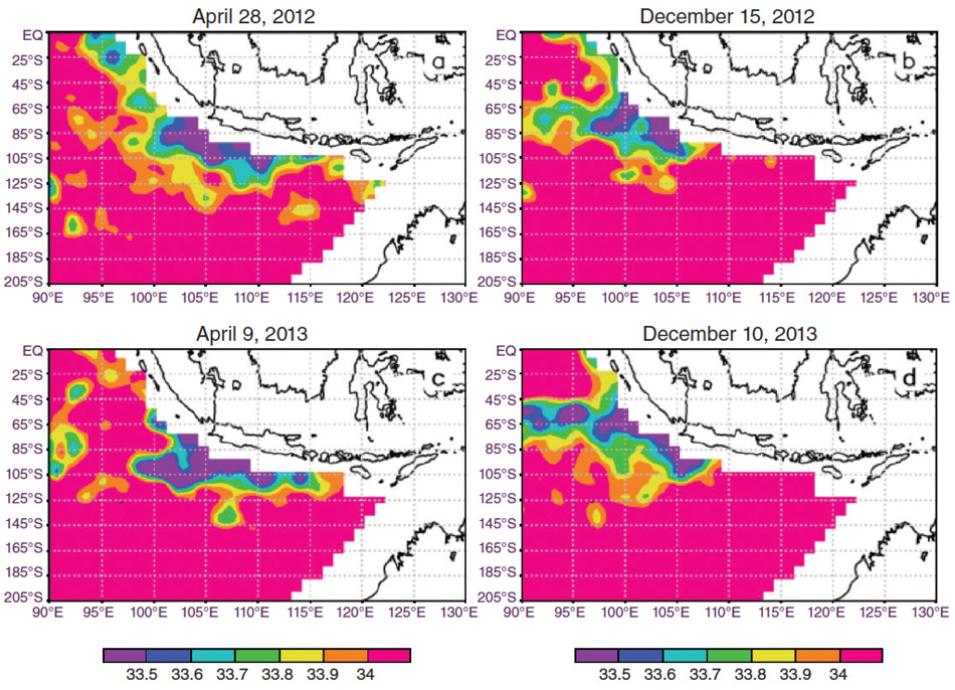

For researchers such as Jim Potemra, who study how oceans circulate and mix near the surface, a new global sea surface salinity-sensing satellite promised a broader, yet closer look at these processes. Still, scientists did not know exactly what the new satellite data might pick up. “When we started gridding the data, we said, let’s have a look at regions where we don’t have a good idea of the surface fluxes. The signal that was coming out of the Indonesian Seas was a little surprising,” Potemra said. It was evidence of a feature that they had mostly imagined.