As we move into the cloud and to a more open, collaborative model, this situation will change from one where we’re talking not just within our existing small academic sphere, but with a broader range of colleagues in a wider range of interest areas. This will bring in a wider range of thought to problem-solving and investigation. We’ll realize that collaboration across great distances and across scientific disciplines is possible in unique and exciting ways.

This is really about building trust at an organizational level, trust that goes beyond an individual DAAC or immediate physical colleagues and moves it to trust and collaboration with, for example, everyone working within the EOSDIS and seeing them all as potential collaborators and as sources for good ideas to help solve the particular problem you are trying to solve—and maybe bring in some problems you might not have even thought about.

Ironically, the current situation that we’re in, with being forced to stay at home and interact remotely through video more often than we’re interacting with colleagues on a face-to-face basis, is similar to the model we’ve been working towards with EOSDIS data for the past 10 years. This use of distributed teams to use data collaboratively is one of our goals, and I feel that now more and more people are starting to catch on not only about how this can be done, but also that productive remote collaboration and problem-solving is not only possible, but fruitful.

What is the structure of the team working to evolve EOSDIS data to the cloud? How will this work influence future NASA missions?

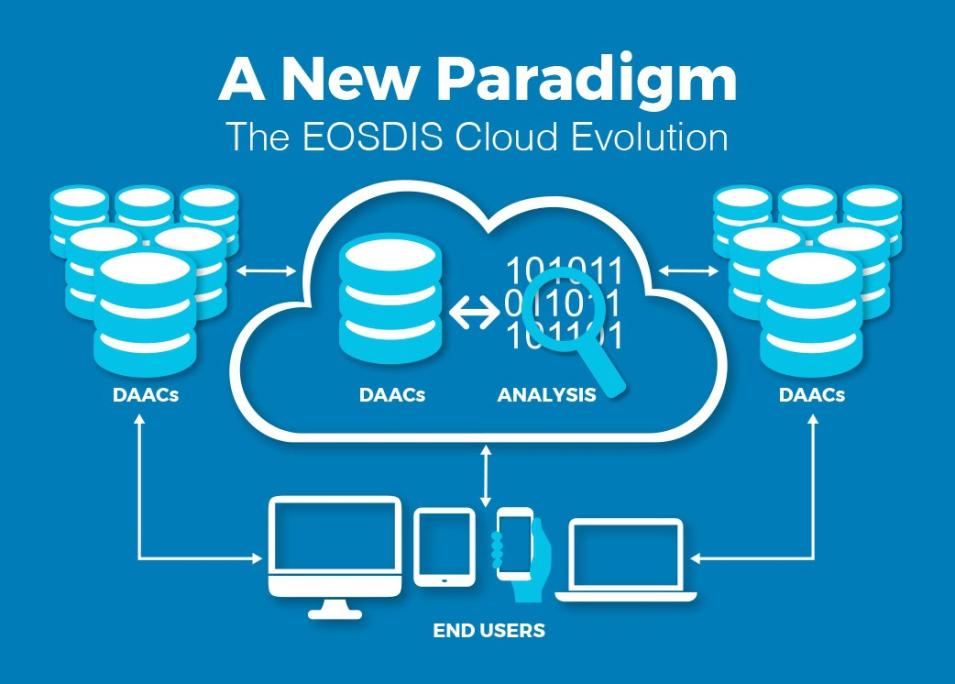

This effort has three primary pillars of activity. There’s ingest and archive, which is my piece, and there’s data use, which is [Chris Lynnes’] piece. The third piece is the underlying platform on which all of this work depends. This work is spread through [NASA’s Earth Science Data and Information System (ESDIS) Project], the DAACs, outside contractors, and even some universities.

The work we do will also influence how future NASA and joint NASA missions are planned, especially on how upcoming missions are looking at doing their data processing in the cloud, like NISAR and SWOT. There are other missions that will generate lessons-learned and a pathway to doing more cloud-native processing as we go forward. I think that we can provide input that could help them with their decision-making process and serve as pathfinders to that end. Our work on the NISAR and SWOT missions is already helping to forge that path.

Twenty years ago, EOSDIS data users were still receiving physical tapes of data in the mail. Ten years ago, they were downloading EOSDIS data using the internet. Now, data and services are becoming available through the commercial cloud. What do you see as the next step in this evolution?

I think that you’ll start seeing a move from information, to knowledge, to wisdom. The natural evolution of the problem space is evolving from hoarding scientific knowledge as proprietary work and into a more open model where we reward things such as creating tools and software that allow end-users to come in and acquire understanding by dynamically exploring the data in real-time.

Another exciting avenue for development involves utilizing machine learning, which is creating [research] opportunities where we can sort of guide the data and guide the machines as they do their work, but also allow the machines to find patterns on their own that were not immediately evident. With Big Data collections like we’re developing and planning for, the human eye can’t look at all the data to parse out these hidden patterns. I’m really excited about pattern discovery and what we can glean from this sort of information about Earth’s changing processes and the direction in which these processes might be going.

Over the next five years, what are you most excited about in terms of how EOSDIS data will be archived and used?

I’m most excited not just about the NASA science that is going on, but also the enablement of science using data products that we already have that can be mashed together or fused together into longer continuity products or into more impactful, higher-level data products that are not just useful to the NASA community, but are also useful for entities like the U.S. Department of Agriculture or [the Federal Emergency Management Agency].

I think that as we see our climate evolve it will be crucial to put data into terms that are not just understandable only to NASA and generally-focused science users, but to communities beyond this, like decision-makers and policy-makers and influential global leadership. I feel that the work that we do is just a small piece of what could change our future and lead to a brighter tomorrow. I think that we can provide the data that will help mitigate the impacts of climate change. This is what makes my work important to me.

How will the commercial cloud help facilitate this?

My favorite advantage of the cloud is not the cloud itself, but what it has allowed us to do as a community by working together. Getting people to work together toward a common goal on a common problem after decades of working on it individually has been a really, really rewarding experience for me. I think we’re all benefitting from the diversity of thought that is brought to the table when we try to consider everyone’s needs.

There’s a good quote that says “when you want to go fast, go alone; when you want to go far, go together.” I think that has been an inspiration to me. We were going fast alone, but I think that now we’re enabling a future where we can go far together.