Ecologists use biomes to classify the global patterns of ecology on land, based on vegetation types that correspond to global patterns in climate. The different biomes—lush tropical forests, hot arid deserts, grasslands, or cold, arid tundra—can each support unique kinds and amounts of life. They also make different contributions to the global carbon cycle.

Like other modern sciences, ecology strives for objectivity by reducing the complexity of the systems they study. One way to do this has traditionally been to isolate human influence from observations, by studying areas presumed to be wild. The lands that we influence, such as croplands and cities, tend to be excluded from consideration, or squeezed into just a few land classifications, where they were largely ignored by ecologists until recently.

But almost seven billion people live on Earth today. “We know instinctively that this is not what the world looks like any more,” Ramankutty said. Ramankutty and Ellis are among a growing number of ecologists who think the classic focus on wildlands does not match the state of the Earth today.

Ellis noted, “What is the ecology that people create and sustain over a long period of time? In the past, this was a very marginal subject for ecologists. If you have people in your ecosystem it’s not really ecology. It’s a degraded thing, an unimportant ruined thing. For me that was always very frustrating.”

People in the map

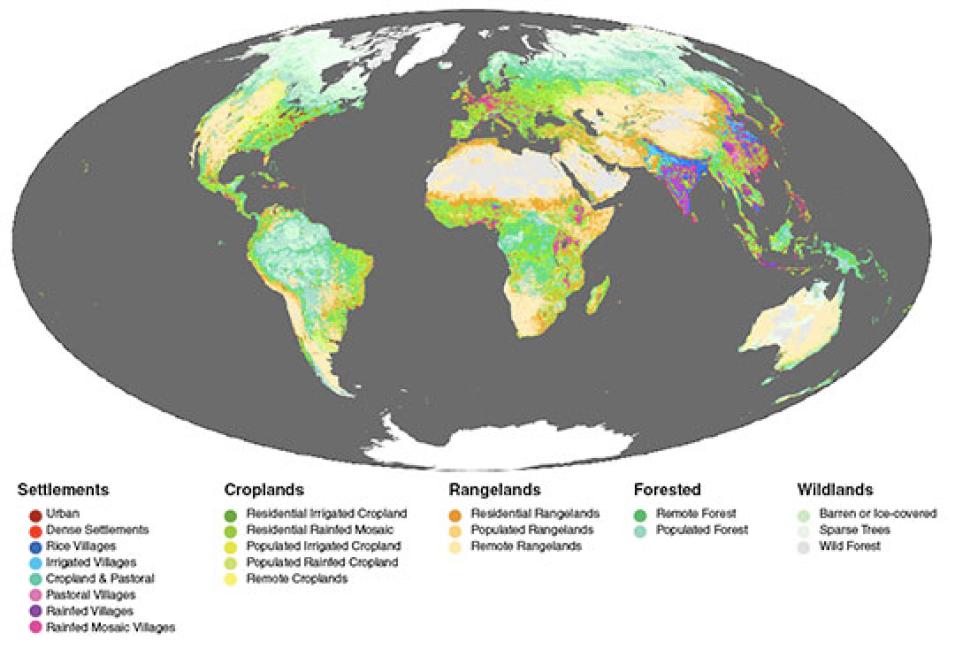

Ellis thought that data could show how much of the Earth is under human influence. “I wanted to quantify and express in a powerful way to ecologists the significance of anthropogenic ecosystems,” he said.

He proposed to Ramankutty, who had been using global data to study patterns of land use for agriculture, that they look at population and land use statistics. Ramankutty said, “The sheer number of people affects ecosystem processes in the village landscapes that Erle had been studying. He thought of extending this idea to a global scale.”

As they melded global data sets on population, land use, and land cover, patterns emerged. Ellis said, “There was no obvious method for determining the big categories of the anthrome system, so we did a statistical approach that figured out the global patterns in these data.” The researchers saw a new biome system, with human-dominated ecosystems that they called anthropogenic biomes, or anthromes for short.

The analysis produced two major insights. Ramankutty said, “First, an astonishing amount of the world’s landscape, up to 77 percent, is an anthrome.” People have taken over most places on Earth that can support human life. Some wildlands remain in rainforests, but most are in cold, arid, northern areas. “Second, we usually think of people living in cities between forests, or between forests practicing agriculture,” Ramankutty said. “We think of our influence as being small. That’s not the way the world works anymore. We currently have human systems within which natural systems are embedded.”

The data also showed more human-influenced categories than just the classic cropland or urban area biomes. Ellis said, “There’s this incredible richness of systems and ecosystems that we create and sustain. For example, in the temperate zone you see trees. Just about every system, urban or agricultural, has trees. We create mosaics; we hardly ever create one thing. When you look at the Earth from space—when you look out of the airplane—you can see it.”

The ecologies of these mosaics were a question mark for researchers. Ramankutty said, “We think that you can have valuable ecosystems in places where humans live. There can be valuable carbon stored in trees in urban landscapes. There are more trees in cropland anthromes than in wildland anthromes. We should measure those things as well.”