Laura Kurgan, Professor of Architecture, Director Center for Spatial Research, Columbia University, Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation

Research Interests: Urban space and conflict; critical data visualization and mapping; environmental justice; spatial inequality.

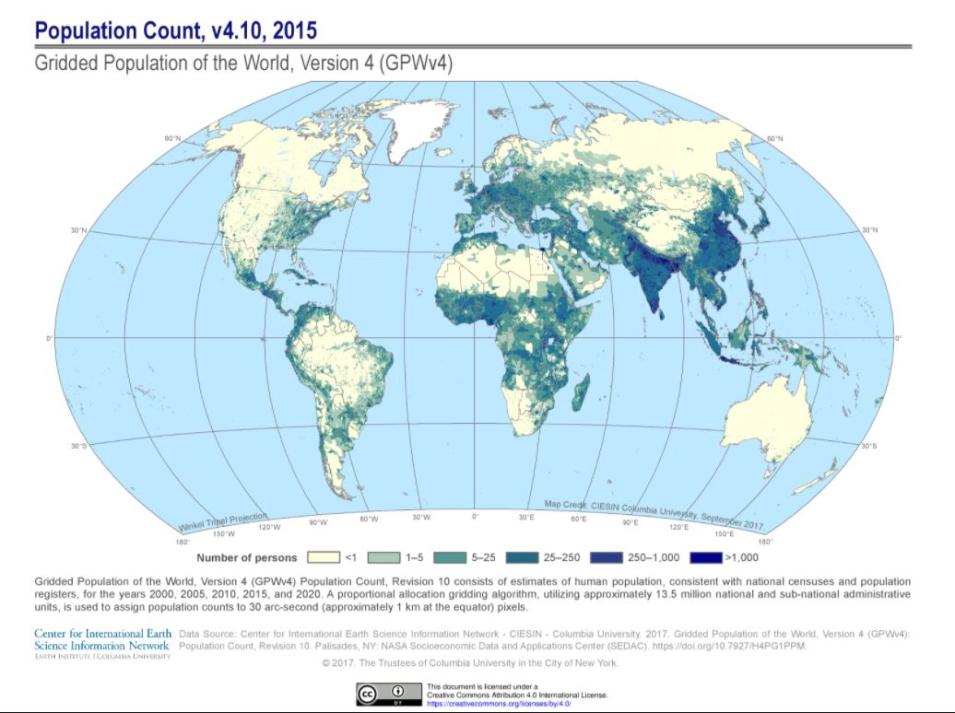

Research Highlights: In the 1960s and 70s, Earth-observing satellites and the data they produced were primarily used to aid weather prediction and monitor environmental change, be it on land, in the surface waters of the ocean, or in the atmosphere. However, as satellite instrument technology advanced, and engineers developed more sophisticated ways of extracting information from the data provided by satellite instruments, the applications of satellite data have grown exponentially. So have the disciplines and fields that find it valuable. Today, the use of satellite data has gone beyond the domains of meteorologists, environmental scientists, and geographers, to include fields ranging from economics to epidemiology to history. Thus, in addition to following severe weather, ocean currents, and atmospheric pollutants, data from Earth-observing satellites are now used to track micro-plastics and commercial fishing fleets, survey gas flares and mining, and monitor urban sprawl and the spread of disease — and the list keeps growing.

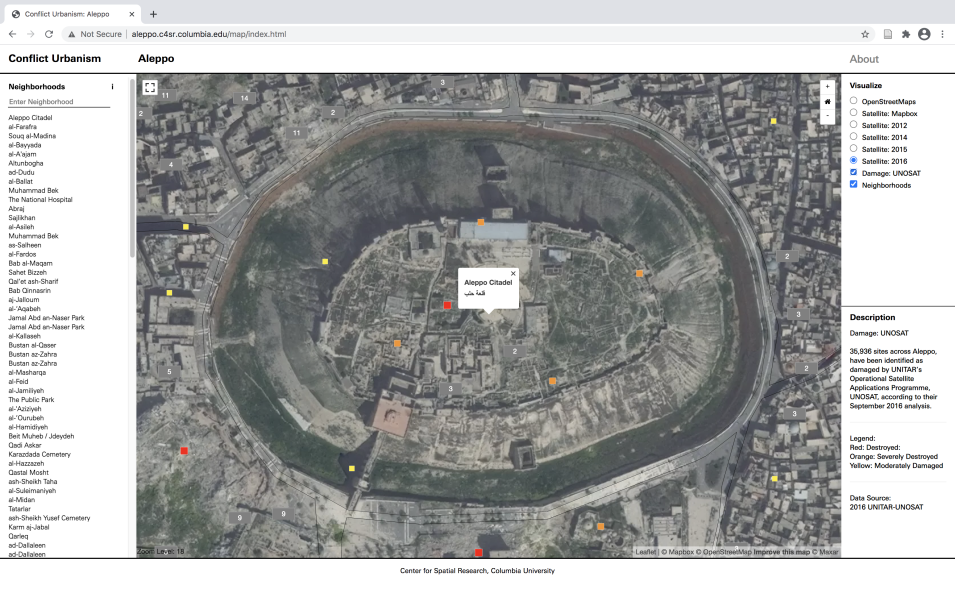

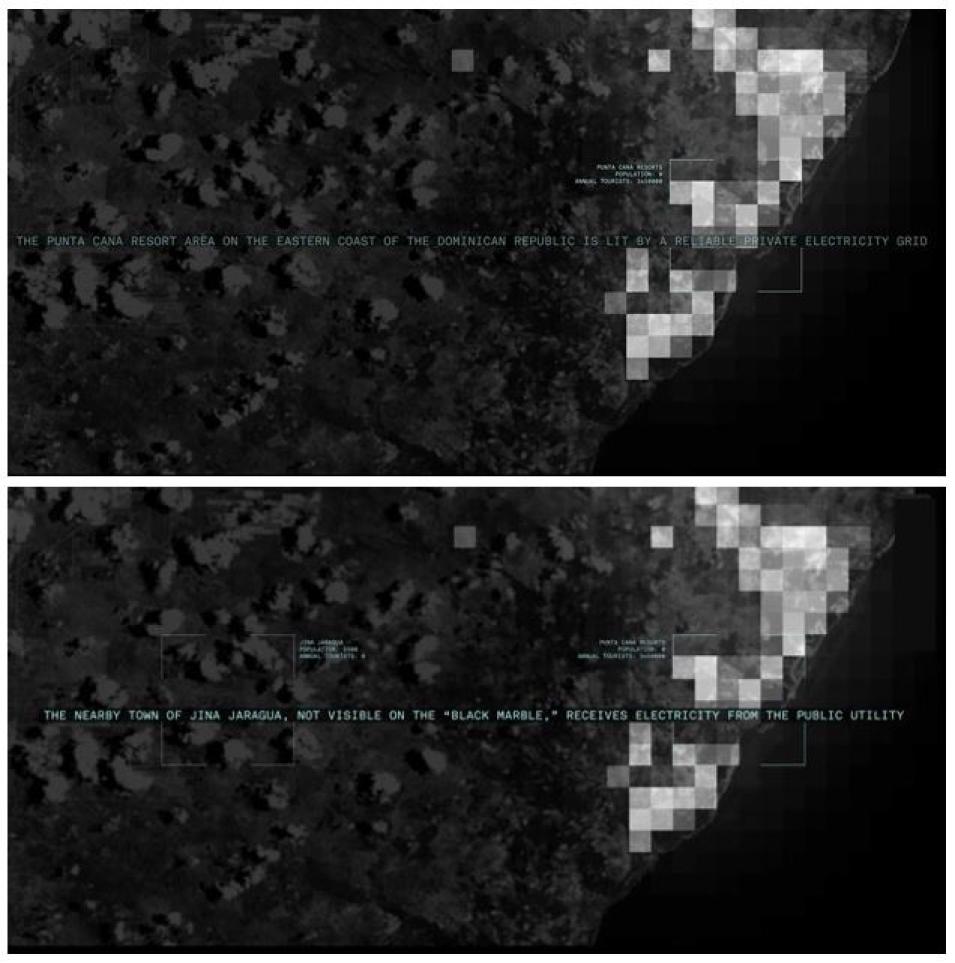

Among those experts using remotely sensed data in new ways is Laura Kurgan, Professor of Architecture at the Graduate School of Architecture Planning and Preservation (GSAPP) at Columbia University, where she directs the Center for Spatial Research (CSR). An architect by training and, by her own admission, “not a data scientist,” Kurgan’s work uses spatial data to investigate political and social conflict, while also exploring the ethics and politics of digital mapping and the technologies used to create it.

“Urban data and, in particular, geo-spatial imagery, are essential for investigating the ways contemporary social and political space is built through contestation. But we need to work with them critically and reflectively, not take them for granted,” Kurgan said.