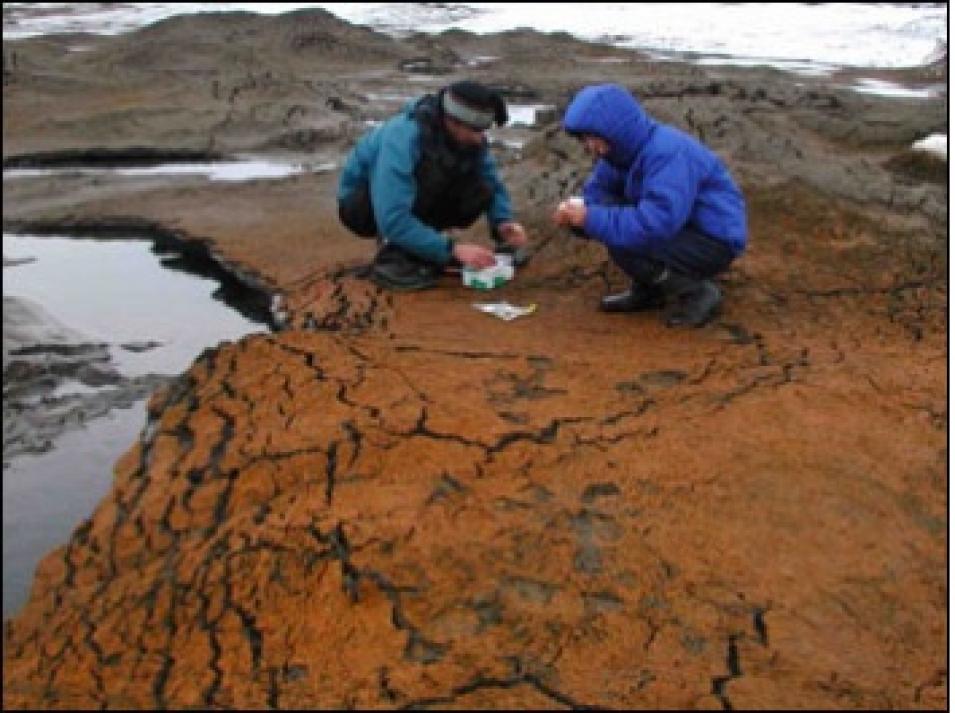

In the summer of 2002, graduate student Derek Mueller made an unwelcome discovery: the biggest ice shelf in the Arctic was breaking apart. The bad news didn’t stop there. Lying along the northern coast of Ellesmere Island in northern Canada, the Ward Hunt Ice Shelf had dammed an epishelf lake, a body of freshwater that floats on denser ocean water. This epishelf lake, located in Disraeli Fiord, was host to a rare ecosystem, and it was the largest and best-understood epishelf lake in the Northern Hemisphere. When the Ward Hunt Ice Shelf fractured, the epishelf lake suddenly drained out of Disraeli Fiord, spilling more than 3 billion cubic meters of fresh water into the Arctic Ocean.

Mueller and his graduate advisor Warwick Vincent, both of Laval University in Quebec City, realized something unusual was happening to the ice shelf when they found unexpected fractures while doing fieldwork on the ice and during helicopter overflights. They contacted geophysics professor Martin Jeffries at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Fortunately, Jeffries had planned ahead.

“Knowing that Derek and Warwick would be doing fieldwork, I’d already placed data acquisition requests with the Canadian Space Agency through the Alaska Satellite Facility Distributed Active Archive Center (ASF DAAC),” Jeffries said. Jeffries requested data from the agency’s RADARSAT-1 satellite. Equipped with a Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) sensor, RADARSAT-1 can acquire imagery in almost any kind of weather, with or without sunlight. “I had almost real-time RADARSAT data on my computer in a very short time, and I could confirm Derek’s observation.”